Pocahontas – On Myth, Memory, and the Meaning of Her Name

Recorded via ChronoTranscriptor™ – September 25, 2024

[Host Introduction]

Today on ChronoTalks, we bring into the present a woman whose name echoes through centuries of history, legend, and distortion: Pocahontas—the daughter of Powhatan, a bridge between worlds, and perhaps the most misrepresented woman in early American memory.

Her real name was Matoaka, though she was called Pocahontas—“playful one.” She lived through violent cultural clashes, captivity, forced conversion, and a voyage across the ocean that would end in her death far from home.

With the help of the ChronoTranscriptor™, we sit with her—not the caricature, but the woman, speaking in her own voice.

[Interview Begins]

Host: Matoaka—Pocahontas—thank you for joining us.

Pocahontas: I am surprised to be called. People have spoken about me for so long, I did not know they still wished to speak with me.

Host: Let’s begin there. You are remembered mostly through stories told by others. What does that feel like?

Pocahontas: It feels like being painted in someone else’s colors.

They told tales of romance and rescue. But I was not a princess in need of saving. I was a daughter, a negotiator, a witness to a world being changed by force.

What they remember is not always what happened. But it is still part of me.

Host: Did you really save John Smith’s life?

Pocahontas: I was a child. Twelve, maybe thirteen. He was a stranger brought before my father. I did what I was taught—to show mercy, to make peace where blood could be spilled.

Whether it was a ritual, a test, or something else entirely... I do not know. But I did not fall in love with him. That part they added like flowers on a grave.

Host: What do you remember about your people?

Pocahontas: Laughter by the river. Smoke curling into the trees. The language of my sisters and the rhythm of drums in the dark.

My people lived with the land, not on it. We gave thanks, not orders. And when the ships came, bringing hunger, metal, and fear—we tried to teach peace. We tried.

Host: You were taken captive by the English in 1613. What was that like?

Pocahontas: At first, it was silence. I did not speak their language. Then came the baptism, the new name—Rebecca—the marriage.

Some say I was a symbol of unity. But unity without choice is only surrender.

I found dignity where I could. I smiled when it was expected. But part of me stayed on the shore.

Host: Do you have any memories of your voyage to England?

Pocahontas: Cold. Stone. Eyes that looked at me like I was a painting come to life. I wore dresses that were heavy with meaning.

They called me civilized, as if spirit comes only in English.

I met kings and queens, but I missed my son’s first steps. That is the cost of being made a symbol.

Host: What would you say to young women today who feel caught between cultures?

Pocahontas: You are not broken. You are woven.

You can carry more than one name, more than one story. But hold fast to your roots, even if the wind blows hard. Let your truth be louder than your legend.

Host: How do you want to be remembered?

Pocahontas: As someone who tried to keep peace when the world was choosing war.

Not as a fantasy. Not as a statue. But as a woman who stood in the river between two nations—and did not drown.

[Closing Remarks]

Host: Pocahontas—Matoaka—thank you for your wisdom, your resilience, and your voice.

Pocahontas: May the next story be told with gentler hands.

Subscribe to ChronoTalks and keep time alive through testimony.

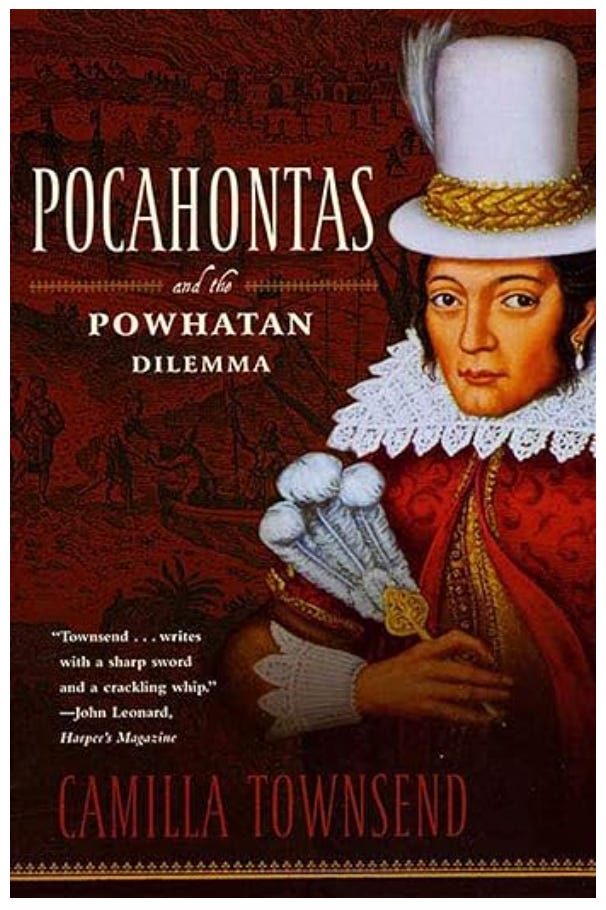

Camilla Townsend’s Pocahontas and the Powhatan Dilemma stands apart from all previous biographies by vividly revealing how seventeenth-century Native Americans—particularly Pocahontas and her people—saw, understood, and navigated their world in ways strikingly similar not only to the English colonists but also to ourselves.

Far from being naïve or passive, figures like Pocahontas and her father, the formidable chief Powhatan, met the arrival of the English with a complex mix of diplomacy, resistance, and calculated force. Townsend portrays Pocahontas not as a mythical peacemaker, but as a strategic actor—keenly aware of the power imbalance and employing every available tool to assert agency: espionage, alliance, negotiation, and defiance. Her life becomes a lens through which we can understand Native American resistance—subtle, courageous, and deeply human.

In Townsend’s hands, Pocahontas emerges in full dimension: as a clever child on the banks of the Chesapeake, a political figure among both her own people and the settlers of Jamestown, and finally, as a poised gentlewoman navigating the courtly intrigues of London. For the first time, we are invited to see her not as a symbol, but as a person—and through her, to see the resilience and complexity of an entire culture. More information…