Mark Twain – On Truth, Humor, and the American Mess

Recorded via ChronoTranscriptor™ 3.2 — April 1, 2025

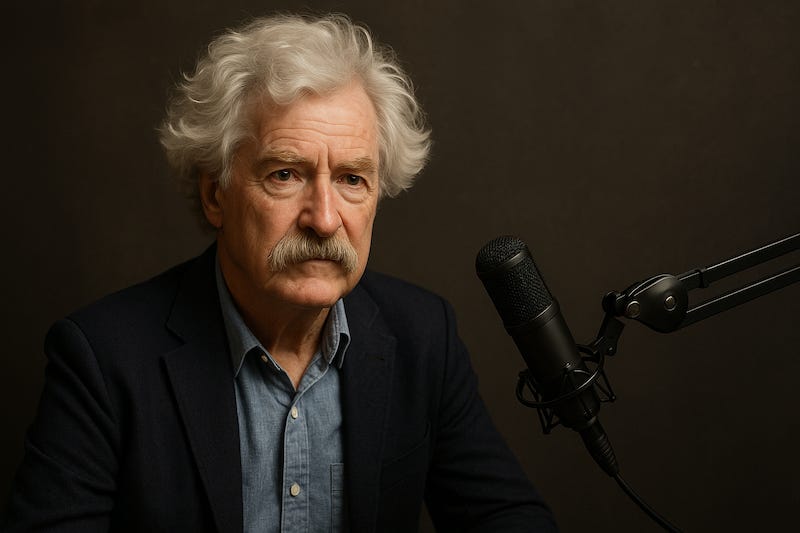

[Host Introduction]

Today on ChronoTalks, we sit down with one of America’s greatest literary minds—and most unfiltered critics—Samuel Langhorne Clemens, better known to the world as Mark Twain.

The author of The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn, Tom Sawyer, and a dozen other enduring classics, Twain wasn’t just a novelist—he was a sharp-tongued observer of hypocrisy, greed, and the absurdities of his time. With the help of the ChronoTranscriptor™, we’ve brought him forward from 1909 to 2025 to ask what he thinks of our absurdities.

Fair warning: Twain never sugar-coated a thing in his life. Why would he start now?

[Interview Begins]

Host: Mr. Twain, thank you for joining us today.

Twain: I was told there’d be coffee. I find none. But the company seems tolerable, so let’s begin.

Host: You’ve been called America’s greatest humorist. Do you think humor still has the same power it did in your day?

Twain: Humor has always been the last defense of the sane against the nonsense of the crowd. In my time, I used it to slip truth past the censors of society. When you tell people the truth, they get angry. When you tell them a joke, they laugh—and then wonder why it stings.

You folks have more jokes now, but less truth in them. Everyone’s trying to go viral, but nobody wants to go honest.

Host: What do you think of today’s political climate—division, outrage, media saturation?

Twain: I think if I were born today, I’d have a thriving YouTube channel and an FBI file.

Your politics are no worse than they were in mine—just louder. We had scoundrels too, we just printed them in black and white. Now you’ve got them in full color, 4K, shouting into your pocket.

But the root's the same: people pretending they’re right instead of trying to be wise.

Host: What about the internet, social media, smartphones—any thoughts on our obsession with them?

Twain: It’s remarkable. You’ve put the Library of Alexandria in every man’s hand, and most of you use it to argue with strangers and look at cats.

Still, I admire it. Communication at the speed of light—though most of what’s being said isn’t worth hearing. You’ve managed to shrink the world and inflate the nonsense. Quite a feat.

Host: Your books, especially Huckleberry Finn, have been both celebrated and banned. How do you feel about that?

Twain: If a book of mine gets banned, it’s a sign that it hit a nerve worth hitting. Huck Finn was meant to scrape the rust off the soul of a country pretending it had no blood on its hands. If that’s uncomfortable, good.

The only books that never offend anyone are the ones that say nothing.

Host: Some of your language and themes have come under scrutiny in recent years. Do you think your work still has a place in today’s culture?

Twain: I wrote the world as I saw it, not as anyone wished it to be. If people want sanitized fiction, they should buy soap, not books.

But I’ll say this: context matters. Teach the books. Teach the time. Teach the pain. Just don’t pretend that avoiding words is the same as curing wounds.

Host: If you could give Americans today one piece of advice, what would it be?

Twain: Read more. Think twice. Laugh once in a while without needing permission.

And stop making celebrities out of idiots. I made a career mocking that kind of thing. You made a society out of it.

Host: What do you hope people remember you for?

Twain: For telling the truth dressed in humor—and for never taking either one too seriously.

If someone reads a line of mine and thinks, “That’s exactly what I was afraid to say,” then I did my job.

[Closing Remarks]

Host: Mr. Twain, thank you for your time, your wit, and your irreverence. It’s been an honor.

Twain: The honor’s mine. Now—about that coffee?

Subscribe to ChronoTallks for more conversations with the past—and all its unfinished thoughts.

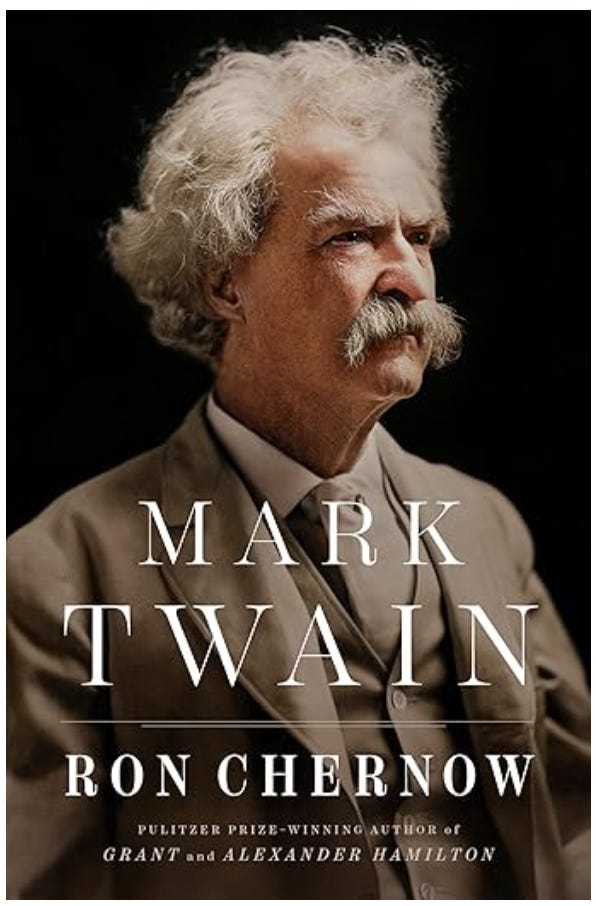

Before he became Mark Twain, he was Samuel Langhorne Clemens. Born in 1835, the man who would become America’s first—and most influential—literary celebrity spent his boyhood dreaming of piloting steamboats along the Mississippi River. That dream came true, but when the Civil War disrupted his life on the river, the young Clemens headed west to the Nevada Territory. There, he took a job at a local newspaper, penning dispatches laced with sharp wit and irreverent humor. It wasn’t long before the former river pilot from Missouri gained national attention—writing under a pen name he would soon make legendary.

In this richly layered portrait of Mark Twain, acclaimed biographer Ron Chernow turns his formidable lens on a man who chased fame and fortune as doggedly as he crafted his public image. After rising to prominence as a journalist, satirist, and lecturer, Twain settled in Hartford with his wife and three daughters, where he wrote The Adventures of Tom Sawyer and Adventures of Huckleberry Finn. He immersed himself in the whirlwind of American culture, emerging as its most outspoken and celebrated social critic. Yet Twain’s boundless ambition led him into reckless financial schemes that ultimately bankrupted him. To recover, he and his family spent nine tumultuous years in Europe. Tragedy followed: the loss of his wife and two daughters shadowed his later years, a period marked by grief, political outbursts, and eccentric behavior that often masked deeper turmoil.

Drawing from Twain’s expansive archives—including thousands of letters and hundreds of unpublished manuscripts—Chernow delivers a masterful portrait of a man whose life mirrored the forces shaping America: westward expansion, industrial upheaval, and war abroad. Twain remains the most important white author of his generation to confront the legacy of slavery with such candor and complexity. More than a century after his death, his voice continues to resonate—quoted, debated, and cherished.

In this profound and brilliantly researched biography, Chernow offers not just a tribute to Twain’s literary genius, but an intimate exploration of a life as singular, contradictory, and unforgettable as the nation he chronicled. More information…