Marie Curie – On Discovery, Doubt, and the Loneliness of Great Work

Recorded via ChronoTranscriptor™ – April 19, 2025

[Host Introduction]

Today on ChronoTalks, we welcome Marie Skłodowska Curie, the pioneering physicist and chemist who changed science—and the world—with her groundbreaking work on radioactivity.

The first woman to win a Nobel Prize. The only person to win in two different scientific fields. A woman who broke barriers, buried her husband far too soon, and kept working until her discoveries quite literally consumed her.

With the help of the ChronoTranscriptor™, we bring Madame Curie into the present to reflect on knowledge, sacrifice, and the quiet price of brilliance.

[Interview Begins]

Host: Madame Curie, thank you for joining us.

Marie Curie: I am told I’ve been dead for nearly 90 years. So it is either a miracle—or science pretending to be one. Either way, I am listening.

Host: Your work fundamentally changed the world. Do you think people today truly grasp what you discovered?

Marie Curie: I do not think people grasp even the nature of discovery itself. We imagine scientists as lightning-struck geniuses—but it is mostly tedium. Dust. Waiting. Fear that you are wrong.

And sometimes, you are.

But the world changed, yes. We isolated radium and polonium with our hands, our lungs, our flesh. We did not know the cost. But we believed the knowledge would illuminate more than it destroyed.

Host: You were the first woman to win a Nobel Prize. How did that shape your life?

Marie Curie: It shaped how others saw me more than how I saw myself. The committees debated—should they give it to a woman? They gave it to my husband Pierre and me together. Later, I would win another, alone. That was… less comfortable for the world.

In the lab, radium does not care whether the hand is male or female. But people do.

Host: You lost your husband Pierre in a sudden accident. How did you carry on?

Marie Curie: I did not have the luxury of stopping. We had children. I had a lab. And grief, when you stir it into work, becomes a kind of fuel.

Pierre was my partner in thought. After he died, I had to carry the weight of two minds alone. I became quieter. But not slower.

Host: Your affair with Paul Langevin sparked scandal. Did it affect your work?

Marie Curie: The scandal did not affect my work. But it affected the air around me—the invitations, the funds, the gaze of men who once called me brilliant now called me dangerous. Or worse: a distraction.

I won my second Nobel Prize in the middle of that storm. They begged me not to attend the ceremony. I went anyway. One does not apologize for intelligence.

Host: What would you say to young women entering science today?

Marie Curie: Do not wait to be invited. Do not soften your voice. Let your questions ring louder than your critics.

The work must be done. Let them call you difficult. Let them call you obsessed. Good. Obsession is how you break the dark open.

Host: How do you feel about how radioactive science has evolved?

Marie Curie: We were idealists. We saw radium as light, as hope, as a cure. We did not yet see Hiroshima. Or Chernobyl.

Science is a child that grows faster than its parent can teach it. What matters is that humanity remains the steward of its own power.

Host: If you could be remembered for one thing, what would it be?

Marie Curie: For being curious—and unwilling to stop. Even when I was told to stop. Even when it hurt. Especially then.

[Closing Remarks]

Host: Madame Curie, thank you for your time—and your brilliance.

Marie Curie: Merci. And take care with your experiments. Especially the invisible ones.

Subscribe to ChronoTalks to journey further through time.

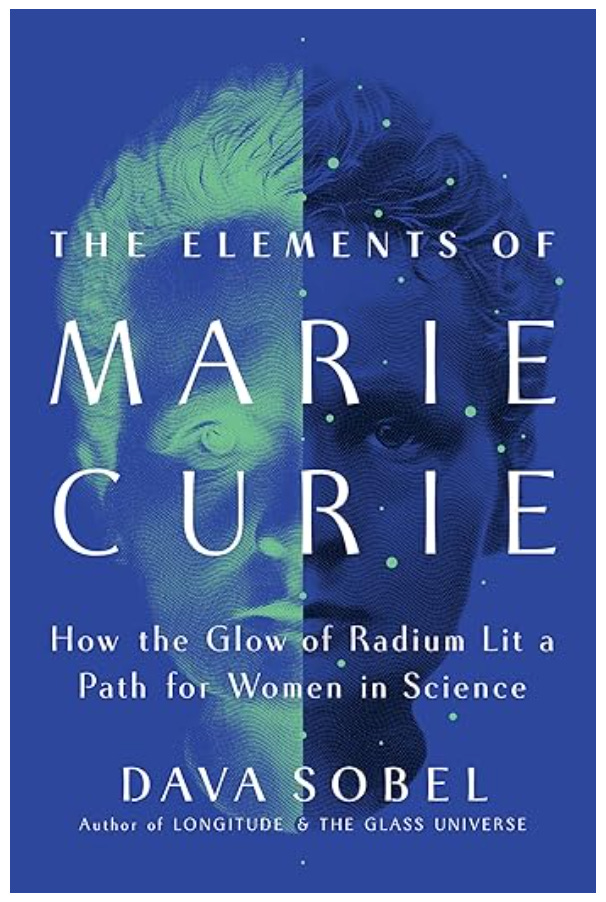

“Even now, nearly a century after her death, Marie Curie remains the only female scientist most people can name,” writes Dava Sobel at the outset of her luminous portrait of the only person—man or woman—ever awarded Nobel Prizes in two distinct scientific fields: Physics in 1903 (shared with her husband Pierre) and Chemistry in 1911 (awarded solely to her). Yet as Sobel reveals, Curie’s brilliance extended far beyond the laboratory. After Pierre’s sudden death in 1906, she succeeded him as professor of physics at the Sorbonne, raised two gifted daughters, and outfitted a van with x-ray equipment to serve wounded soldiers on the front lines of World War I. She befriended Einstein, earned the respect of world leaders, and became a role model for generations of aspiring women scientists.

As she did so memorably in Galileo’s Daughter, Sobel brings a fresh perspective to Curie’s life, framing it through the stories of the women she inspired—among them France’s Marguerite Perey, who discovered francium; Norway’s Ellen Gleditsch; and Curie’s own daughter Irène, who shared the 1935 Nobel Prize in Chemistry. Often the only woman present at scientific gatherings exploring the atom’s mysteries, Curie traveled tirelessly—even while battling chronic illness—to share her discoveries about radioactivity, a term she herself coined. Her U.S. lecture tours drew enormous crowds, though she remained modest and self-effacing. Only later did her daughters realize, as Ève recalled, “what the retiring woman with whom they had always lived meant to the world.”

With the narrative grace that made Longitude and Galileo’s Daughter bestsellers, and the reverence for women in science that animated The Glass Universe, Sobel delivers a radiant biography—an intimate, compelling portrait of one of the most influential figures in modern history. More information…