Leonardo da Vinci – On Curiosity, Invention, and the Weight of Genius

Recorded via ChronoTranscriptor™ 3.2 — April 15, 2025

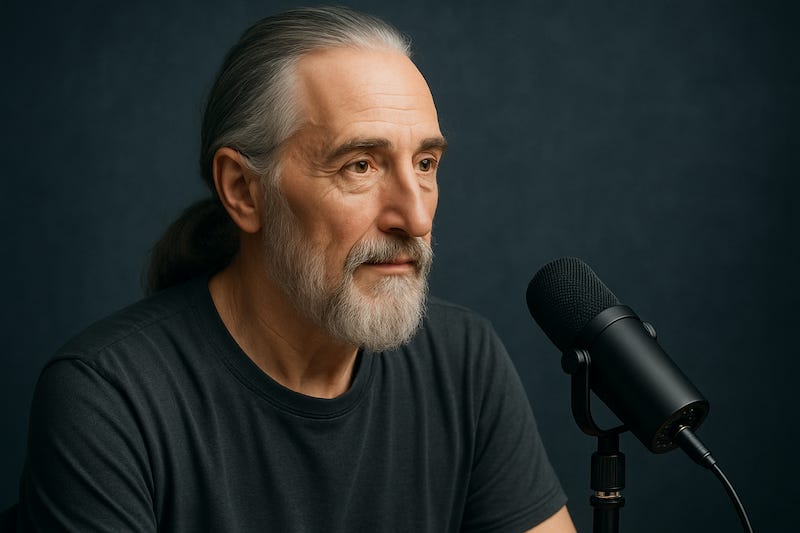

[Host Introduction]

Today on ChronoTalks, we meet the man who perhaps best defines the word “genius”: Leonardo da Vinci. Painter, inventor, anatomist, engineer, and philosopher—his notebooks spanned everything from flying machines to water flow to the curvature of the spine.

Born in 1452, da Vinci imagined things centuries before they became reality. What would such a man think of a world in which many of his visions have come to life?

Thanks to the ChronoTranscriptor™, we invited Leonardo into 2025 for a conversation about invention, doubt, and the dangers of knowing too much too fast.

[Interview Begins]

Host: Leonardo, welcome. It’s a true honor to speak with you.

Da Vinci: It is a strange world you’ve made—but it glows with wonders. I would like to take it apart and see how it works.

Host: You were an artist, a scientist, a dreamer, an engineer. How did you manage to do so much in one lifetime?

Da Vinci: Curiosity never let me sleep. Every question opened ten more. The world is not made of subjects—it is made of connections. I could not paint without knowing the anatomy beneath the skin. I could not draw a machine without knowing the laws that made it turn.

In truth, I feel I did too little. I left more sketches than sculptures, more notebooks than machines. I was always beginning, always reaching.

Host: Many of your inventions were never built in your time—flying machines, armored vehicles, hydraulic tools. What do you think of modern technology?

Da Vinci: You have given wings to men. You carry voices through the air. You have made light into thought and sent it across the globe. I am awed.

But I also see that the machine moves faster than the mind. You create marvels, but not always meaning. Invention should serve understanding—not distraction.

Host: You were famous in your time for leaving projects unfinished. Was that a flaw, or a choice?

Da Vinci: Perhaps both. I was drawn to beginnings. Completion felt like a narrowing of possibility. A finished painting is one vision. A sketch is still alive—it breathes with what it might become.

But I know it frustrated those who paid me. I preferred wonder to deadlines.

Host: Today, you’re seen as the archetype of genius. Do you believe in the idea of genius?

Da Vinci: I believe in attention. Genius is not a divine spark—it is the long, faithful labor of looking. A child who watches an ant may know more than a king who ignores his map.

I observed. I copied. I failed. And I asked the same question each time: Why?

Host: What advice would you give to today’s inventors and thinkers?

Da Vinci: Look with new eyes. Begin with no assumption. The world will offer you answers, but only if you ask better questions.

Do not confuse speed with progress. Do not confuse knowledge with wisdom. And above all—draw.

Even your machines should begin with the hand, not the algorithm.

Host: If you could start over today, in this modern world, what would you pursue?

Da Vinci: I would study your machines, your sciences, your sky. I would take apart your rockets and your computers. But in the quiet hours, I would still return to the riverbank with my sketchbook.

Art and science—together, always.

[Closing Remarks]

Host: Maestro da Vinci, thank you for sharing your insights. Your work continues to inspire the world.

Da Vinci: Then I have succeeded—not in finishing, but in beginning something that never ends.

Subscribe to ChronoTalks for more interviews across time, space, and the human spirit.

Drawing from thousands of pages of Leonardo da Vinci’s extraordinary notebooks and the latest revelations about his life and work, Walter Isaacson crafts an intimate and vivid portrait of the Renaissance master. As the San Francisco Chronicle notes, Isaacson “deftly reveals an intimate Leonardo,” weaving together his art and science in a compelling narrative. He demonstrates that Leonardo’s genius wasn’t simply innate—it was grounded in qualities we can cultivate ourselves: boundless curiosity, meticulous observation, and a wildly imaginative mind that often danced on the edge of fantasy.

Leonardo created two of the most iconic paintings in history—The Last Supper and the Mona Lisa—yet his brilliance extended far beyond the canvas. He obsessively pursued studies in anatomy, fossils, birds, the human heart, flying machines, botany, geology, and military engineering. He explored the mathematics of optics, investigated how light enters the eye, and used these insights to create shifting perspectives in The Last Supper. His unique ability to merge art and science—epitomized by his Vitruvian Man—placed him at the intersection of disciplines, earning him the title of history’s most creative genius. More information…